If you’re a classic literature reader like I am, there’s a chance you pay at least a little attention to copyright law. A lot of classics are in the public domain, meaning that people can pretty much do whatever they want with them, explaining how the world ended up with something like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. But you might be wondering how public domain works and why there seems to be a sudden explosion of The Great Gatsby everywhere you turn. Let me explain.

First off, what exactly do I mean by public domain, you might be wondering. The Stanford University Libraries explain that public domain: “refers to creative materials that are not protected by intellectual property laws such as copyright, trademark, or patent laws. The public owns these works, not an individual author or artist. Anyone can use a public domain work without obtaining permission, but no one can ever own it.” So, for instance, no one holds the copyright for Pride and Prejudice, and if I want to write, publish, and charge money for a book about Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy opening a pie shop, I can do that, because Jane Austen’s novel belongs to the public and I am a member of the public. Now, once it’s published, my book would have its own copyright, just like, say Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary, which is why I can’t publish a novel about Bridget and Mark Darcy opening a pie shop.

How do works enter the public domain? There are a few different ways, but the one I think that’s most interesting is by the copyright expiring. After all, once upon a time, Jane Austen did own the copyright to Pride and Prejudice, but neither she nor her heirs do now. How did that happen? Well, that’s kind of complicated and has changed over time and differs from country to country. Let’s just focus on US copyright as it stands right now.

For a lot of the 20th Century, published works were under copyright for 28 years, assuming their creator filed for a copyright. At the end of that time, the person who held the copyright could file an extension for another 28 years. After that, it belonged to the public. But then new laws were passed, and copyright was extended for works published in or after 1923 for 95 years after their publication. Practically, what this meant was that between 1998 and 2018, new works did not enter the public domain because of expiring copyrights.

Then on January 1, 2019, works published in 1923 entered the public domain. This was exciting for the simple fact that new works were at last available for the first time in a very long time. Some great novels were including in this batch, such as Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot mystery The Murder on the Links. And because copyright law applies to film and music as well, it meant that in 2019, classic cartoon Felix the Cat entered the public domain along with the song “The Charleston.” On January 1, 2020, creative works from 1924 saw their copyrights expire, which, again, was very exciting.

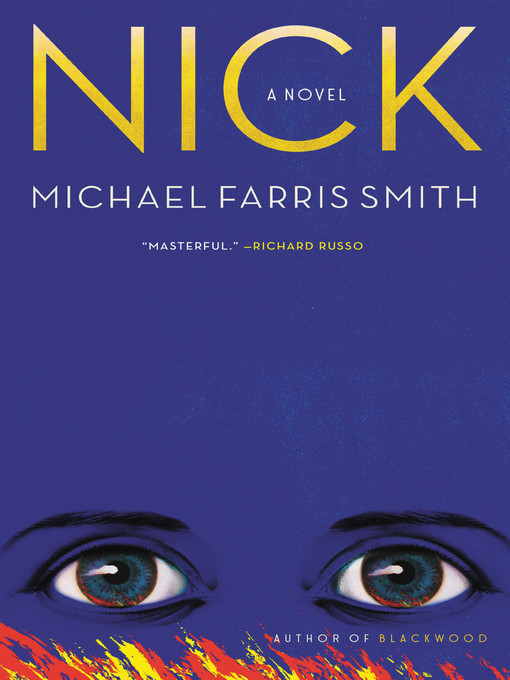

But January 1, 2021 was a day a lot of public domain watchers (and publishers) had been eagerly anticipating, because works from 1925 entered the public domain, and that includes F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Little, Brown and Company was ready, and on January 5 they published Nick by Michael Farris Smith, a prequel novel to The Great Gatsby about Nick Carraway. Coming later this year, there will be a graphic novel adaptation as well as a novel in which Gatsby dislikes daylight, garlic, and mirrors, from which you can probably draw your own conclusions. And in the realm of the truly unique, the fanfiction website Archive of Our Own has a version of Fitzgerald’s classic with every instance of “Gatsby” replaced with “Gritty,” the Philadelphia Flyers’ mascot.

And that, of course, is just this year. If you want to cash in on the works that will soon see their copyrights expire, start working on that adaptation of The Sun Also Rises (2022), Steppenwolf (2023), and Lady Chatterley’s Lover (2024).

Shelia

For more information on copyright and public domain, try the Duke Law School Center for the Study of the Public Domain.

For more about the rise in adaptations and new editions of The Great Gatsby, this New York Times article is a good source.

Leave a Reply